The Siege of Deir Ez Zor

The conflict in Eastern Syria has been under reported from the side of the Western Media. Most news coverage has centred around Aleppo and other fronts in Western Syria. Nonetheless, whilst the Siege of Aleppo was broadcast around the world with horrific images, another siege has been on going in Eastern Syria since 2014 with over 100,000 civilians besieged by ISIS. The aim of this analysis will be to look at the dynamics of the conflict in Dier Ez Zor and as a result convey the nuances of the conflict. This will help shed light on the Syrian conflict which is regularly simplified through the prism of a battle ground between two geo-political powers. Deir Ez Zor is of significant importance currently due to the withdrawal of ISIS forces from Raqqa and Mosul towards the Eastern Syrian Desert.

In the first years of the Syrian conflict many reports would simplify the conflict as one that was fought between a regime that is mostly supported by Alawites against an armed opposition which was mostly Sunni. Maps which showed the various warring factions and the territory held by the opposition during the 2012-2013 years would to some extent prove this assumption. During the years of 2012/2013 the cities of Aleppo, Homs were on the verge of coming under rebel control while cities such as Latakia and Damascus where firmly under the control of the Syrian government. This led media outlets to characterize the war as a purely sectarian war that was fought by a ruling Alawite elite against a majority Sunni population. The reality couldn’t be further from the truth. A complicated mix of various political, military, ethnic, tribal, religious factors has led each battlefield to be different. For example, the same factors that play a role in the Damascene countryside will have no effect in far eastern parts of the country such as Deir Ez zor and Hasakah.

Since 2013, Russian involvement, Iranian backed militia’s along with Palestinian and local forces attached to the Syrian Army have played a key role in turning the tide of the Syrian Civil War. The below analysis will touch upon the factors as to how a city so far from Damascus still remains under government hands. The analysis will also look at the tribal politics that play a part in Eastern Syria. Conclusively, by touching upon these factors the reader will understand how complex the situation on the ground is within Syria.

The Military and Humanitarian situation in Deir Ez Zor – Legitimate Questions

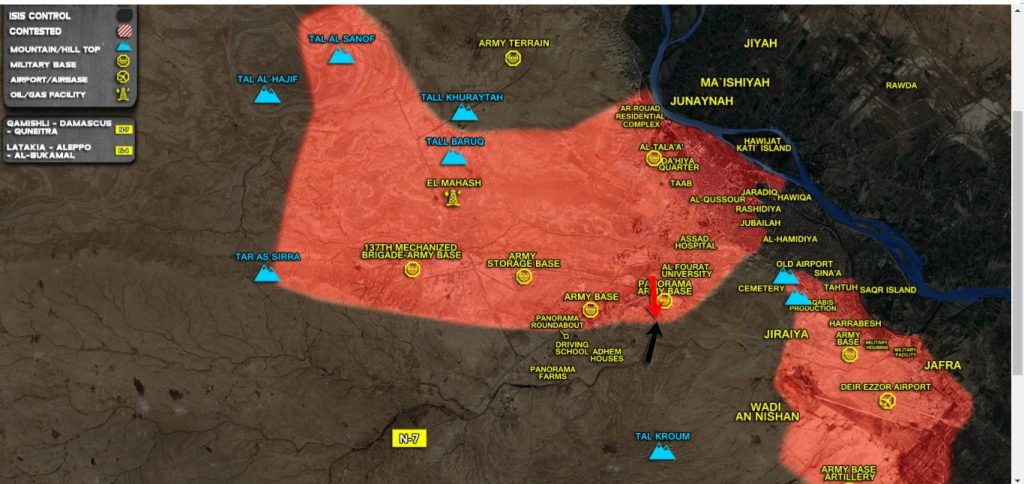

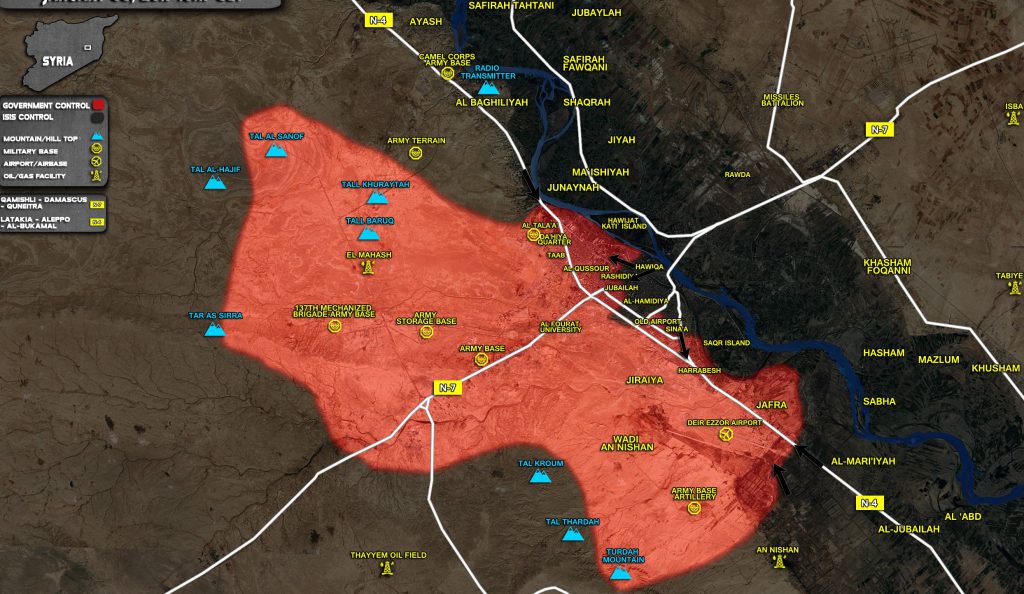

The humanitarian situation reflects the number of years Deir Ez Zor has been under siege from Isis among other groups since 2013. Currently, the only humanitarian aid that reaches Syrian government held areas come via flights from Qamishli and Damascus. SAA troops control about 40% of city’s territory, with 100,000 inhabitants. IS controls the rest, with 50,000 inhabitants. After the early January Isis offensive Deir Ez Zor was split into two government held pockets. This cut resulted in the separation of the Deir-ez-Zor airport and the two eastern neighborhoods (Harabesh and Alrasafa).

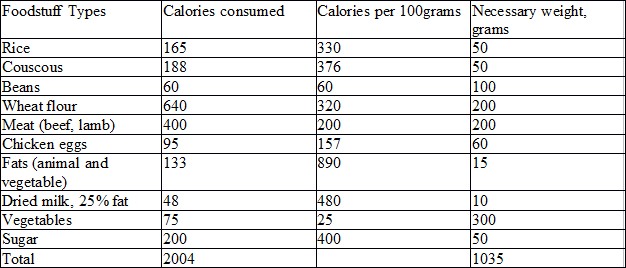

Resupplying the city is arduous and expensive task.The government held pockets are resupplied by the Syrian and Russian aircraft, nonetheless, the world health organization on occasion supply the aircraft with aid. The Syrian government forces are generally tasked with the supplying the city with Russian aircraft intervening in emergency situations. The following picture shows the breakdown of calorie intake based on one civilian in Deir Ez Zor.

Based on the calculations above in January 2017 the city needed 107.5 tons of food per day. 100 tons for the civilian population and another 7.5 tons for the military population. It should be noted that with the deployment of pro-government Palestinian militias along with Syrian Army reinforcements in May 2017 food requirements are significantly higher. For such a task two Ilyushin planes are required to fly from Damascus or Qamshili daily. This provides 80 tons daily to the city, the rest of the aid is provided using Mi-8 helicopters that fly from the Tiyas Airbase. Nonetheless, it takes half a day to unload one Ilyushin plane and fighting near the area of the airport regularly delays food supplies. Thus the above targets in regards to transportation of food are regularly not put into practice.

As a result, the food that does eventually reach Deir Ez Zor is subject to tariffs implemented to pro-government militias. The infographic below shows the price comparison between food commodities in Damascus and Deir Ez Zor in 2016. It should be noted that these prices regularly fluctuate depending on the prices the pro-governement militias impose and the quantity of aid coming into the city.

More recently the World Health Organisation reports that in May 2017 , one litre of diesel was higher by more than six-fold in besieged markets of Deir-ez-Zor (SYP 2,000/L) compared to Damascus markets. Also the prices of rice decreased by 60 percent compared to April, mainly due to food assistance distribution. It is reported that civilians regularly have to pay bribes if they wish to be airlifted outside of Deir Ez Zor. Collectively the situation in Deir Ez Zor is rapidly escalating due to Isis reinforcements who have fled Mosul and Raqqa.

Tribal Aspect of the conflict in Eastern Syria

The conflict in Eastern Syria has a distinct tribal element. When the chaos of war undermined the stability of the region naturally the inhabitants of the Deir-Ez-Zor government fell back on their tribal ties. Nonetheless, since Syria’s independence from French colonial forces the influence of tribes upon regional political dynamics had decreased due to a number of reasons. Initially, during the French Mandate the state would enrich tribal leaders by offering them large plots of land. This cliental relationship ended with the French mandate in 1946. Soon after, the Baath party brought through sweeping efforts to destroy such state-tribal relationships as it wanted to destroy existing class structures. Another reason for the weakening of tribal identity in Eastern Syria came from industrialization. A general migration from the countryside to the various towns and cities within the Dier Ez Zor governante meant that tribal members were less reliant upon kin ties for their needs. The Syrian state apparatus over a number of decades lessened the impact tribes had on local politics. Industrialization along with the Baath party’s aim to influence various tribal members and establish client relationships helped with the process of “de-tribalisation”.

Tribes –

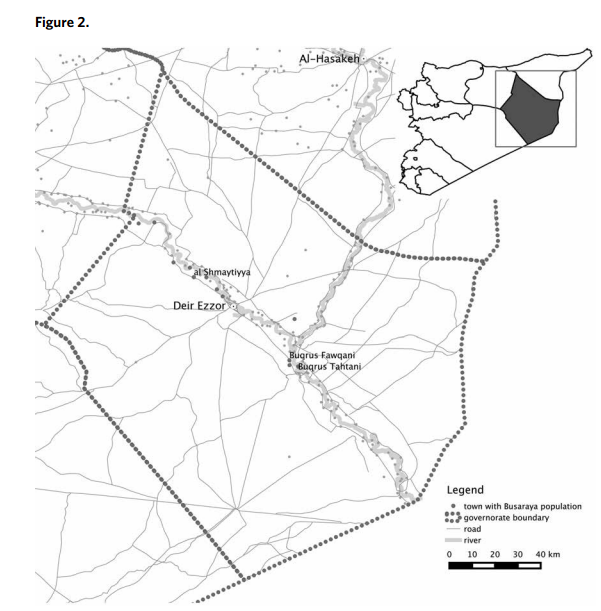

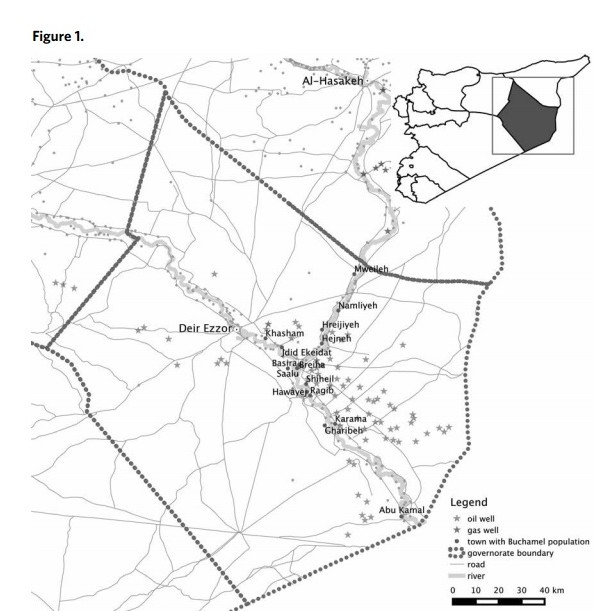

Due to favorable agricultural conditions most towns and settlements in the Deir Ez Zor governent are located on the banks of the river Euphrates. The following tribes populate the Deir Ez Zor state.

Shuaitat

Mostly reside in Abu Hammam, al-Kashkiyah, and Ghranij.

Buchamel clan (holds different clans such as Bukeyr clan (which itself has branches such as Anabeza, Mishrif, Kabesa) , Hifl Clan / Saleh al-Hamad

Reside in (See figure 1 on page 12)

Busaraya (loosely related to the Aqeelat tribal confederation) – Many joined the Syrian government while some joined FSA, Nusra and eventually the Islamic State. The Busaraya tribal leader Muhanna al-Fayyad was elected in parliament in 2012.

The analysis will look at the Shuaitat tribe, clans within the larger Buchamel tribe and the Busaraya tribe. The case studies on these tribes will look at the regional specifics that take place in Eastern Syria. These case studies will touch upon tribal dynamics among other factors such as oil economics, opportunism and revenge.

One tribe – two tows – The case of Al Shmaytiyyeh and Buqrus

The Busaraya tribe is an example of how tribes can split in terms or allegiance to each other due to local conditions. Most of the Busaraya tribe is located in towns east of the city of Deir Ez Zor (see figure) such as Al-Shmaytiyyeh . Nonetheless, the local situation in the town of Buqrus during 2013 is an example of how the Busaraya tribe had to ally with the surrounding villages as to prevent their town becoming a pocket of government supporters surrounded by opposition fighters.

In October 2013, members of the Ahrar Al-sham opposition group overran Al Shamaytiyyeh and arrested 70 people, mostly individuals from the Busaraya tribe. Nonetheless, the citizens of Buqrus east of Deir Ez Zor did not mobilize in defense of their tribe. Buqrus, was surrounded by anti-government forces who were mostly from the Bukeyr tribe. Thus, the local identity of the Busaraya tribe in the town of Buqrus was of more interest than its tribal identity. This shows us that many tribal actors adapt to various specifics in their region.

Massacre of the Shaitiat tribe

The events that led up to the massacre of the Shaitat tribe in Abu Hammam a town west of Deir Ez Zor is an example of how tribal politics have had an effect on the conflict in Eastern Syria. Previous to the Islamic State’s takeover of Mosul in June 2014 the Shaitiat repelled various IS attacks. Nonetheless, a truce was organized in July 2014 whereby IS was permitted to hold an armed presence in the area while local leaders would still hold power. Soon after a tribal member shot and killed an IS member at a local checkpoint in response to hearing his brother was flogged for smoking. (source Washington post) The local was then caught and publically executed. This caused outrage among the residents of Abu Hammam who then overran the IS garrison in the town. Soon after in August 2014, IS returned and proceeded to execute over 700 men over the age of 15 (the death toll is estimated from 400-1000). IS filmed the massacre in an uncut video, methods included beheading and crucifixion. The Shuaitat blamed the Bukeyr for the massacre as many of the latter’s members joined ISIS. The massacres resulted in many Shaitiat tribe members allying with the Syrian Government. As a result, the Syrian government has trained members of the Shaitiat tribe in Palmyra. The tribe also operates as an extension of the SAA in the besieged areas of Deir Ez Zor. The tribe is composed of 100% Sunni Muslims and is allied with the Syrian government based in Damascus 450km away.

Buchamel Tribe – Tribal identity and mobilization – Localization, economics and self-interest

The following case study will look at the Buchamel tribe and how its members would at times use its tribal identity to de-escalate situations while in other areas the tribal identity of certain groups failed to attract support from related kinsmen. As a result, for the purpose of analysis we will use the term localization when describing situations whereby tribes do not mobilise on the convention notion of tribal solidarity. As described earlier on in the analysis, the tribal reliance on the government meant that when state structures collapsed in the 2012-2013 period there was no large mobilization of forces based on tribal ties (apart from the shaitiat tribe in response to a large massacre). A good example of this is the conflict between Buchamel members in the town of Khesham.

The Buchamel tribe are based close to many oil fields within the Deir Ez Zor province. Prior to coalition bombing in 2014, three quarters of the Islamic State’s oil revenue (between 1-3 million USD per day) came from the Deir Ez Zor province. As a result, the locals reaped huge benefits in the period between state collapse and the subsequent IS takeover. In accordance with their economic interests many local militias worked vis-a-vi with Jabat al-Nusra prior to the IS takeover of the region, nonetheless, such alliances would constantly break down due to economic/material interests. Haweidi al-Dibaa a local militia leader came from the Anabeza branch of the Bukeyr clan (which itself belongs to the Buchamel tribe) based in Khesham. Nonetheless, his group operated mostly out of self-interest rather than along tribal lines. This can be seen through his groups aim to regulate electricity to the Deir Ez Zor government by cutting it off and reinstating it only after payment.

Jabat-al-Nusra members from the Saleh al-Hamad branch of the Buchamel tribe soon after in November 2013 arrested Al-Dibaa. The locals interpreted this as an attack on their town Khehsam and the Anabeza branch of the Bukeyr clan. Even though both their lineages eventually both link to the larger Buchamel tribe. This tribal tie did not help them avert conflict. In January 2014, Jabat-al-Nusra shelled the town and its residents. Other members of the Bukeyr clan in other towns did not mobilise to assist their fellow tribesman in Khehsam. This shows us that localization existed well before the eventual IS takeover in mid-2014.

Another example of local allegiances switching based on material benefit is the case of Amr al-Rifdan. Al-Rifdan came from the Mishrif branch of the Bukeyr clan. Rifdan controlled the Conoco oil field one of the largest and most profitable in Syria. Rifdan would provide Jabat Al-Nusra with a portion of the profit received from the oil wells he controlled. Nonetheless, soon after in 2014 the Islamic State offered a more lucrative deal to Rifdan. As a result, Rifdan switched sides. These events led many individuals from the Bukeyr clan to join the Islamic State.

Situations such as the above led Jabhat al-Nusra to fight against the Islamic state in the town of Al Buseyra after the former requested that their members be released from an IS holding facility. This fighting continued until the Islamic State took the fighters stronghold of Shuheil in July 2014.

Conclusion

The above case studies show the process of localization in the Deir Ez Zor state. A complex mix of economic, tribal and identity politics factors all play a part within the conflict in Eastern Syria. The reaction of the Shaitat tribe towards the Islamic State is an example of where conventional notions of tribal solidarity worked towards mobilizing against the Islamic State. The case of the town of Buqrus and how its residents choose to identify themselves with neighboring towns as opposed to their tribal brethren in Al Shamaytiyyeh is an example of where conventional notions of tribal solidarity played no part in the conflict. The final case study on how economic self-interest played a role in how militias allied with groups such as IS and Jabat al-Nusra. Such dynamics in the conflict show how the narrative of a sectarian war taking place in Syria is wrong. All of the above case studies took place in parts of the country that where 500km away from the Syrian government in Damascus.

Sources

“How Do Residents of Deir Ez-Zor See Events in Their City?” Enab Baladi. How Do Residents of Deir Ez-Zor See Events in Their City? 2017-01-22 11:03:26 AM Enab Baladi Enab Baladi, 24 Jan. 2017. Web. May 2017.

Khaddour, Kheder. “The Assad Regime’s Hold on the Syrian State.” Carnage Middle East Centre 8 (2015).

Khaddour, Kheder, and Kevin Mazur. “EASTERN EXPECTATIONS.” (2017).

Kittleson, Shelly. “Tribal Massacre Victims Forced to Negotiate with IS.” Al-Monitor. N.p., 23 July 2015. Web. May 2017.

Kozak, Christopher. “This Is the Assad Regime’s Military Strategy for Winning the Syrian Civil War.” Business Institute. Institute, 28 Apr. 2015. Web. May 2017.

Limam, Gianluca Mezzofiore Arij. “Syria: Isis Executes Al-Sheitaat Tribe Teenager with Bazooka in Deir Al-Zour.” Washington Post. Washington Post, 21 May 2015. Web. May 2017.

“Residents of Syria’s Deir Ez-Zor Fear IS Massacre.” Al-Monitor. N.p., 01 Mar. 2017. Web. May 2017.

Shaheen, Kareem. “Islamic State Surrounds Military Airport in Deir Ez-Zor, Eastern Syria.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 17 Jan. 2017. Web. May 2017.

Sly, Liz. “Overlooked Syria Bloodbath Fuels Resentment of U.S. Campaign.” The Washington Post. WP Company, 20 Oct. 2014. Web. May 2017.

“Syria’s Forgotten Siege: The Noose Tightens around Deir Ezzor.” IRIN. N.p., 01 Feb. 2017. Web. 12 June 2017.

Thompson, Chris. “Islamic State Retreats from Palmyra amid Stunning Syrian Army Offensive.” AMN – Al-Masdar News | المصدر نيوز. Al Masdar News, 02 Mar. 2017. Web. May 2017.